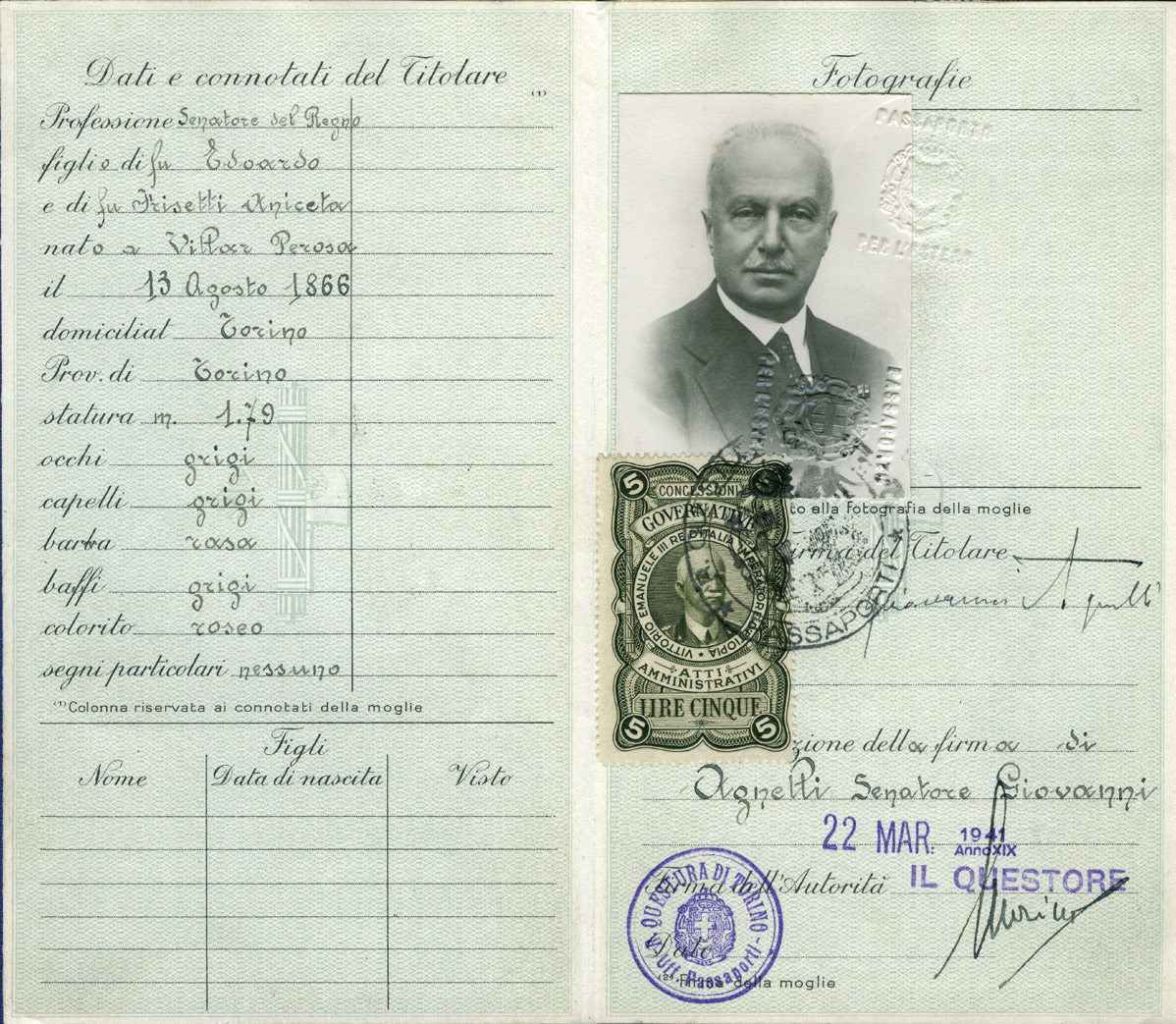

In January 1924, Vittorio Bonadé Bottino – an engineer from Turin who would become the main architect of Fiat’s industrial organization – had his first professional encounter with Giovanni Agnelli, on which his professional future would depend. Bonadé Bottino later confessed that, having been warned one evening that the meeting with the Senatore would take place the following morning at eight o’clock, he was so troubled by the summons that he spent “from half past seven to eight o’clock on a cold and foggy morning […] walking along the avenue of lime trees in Valentino Park” to prepare himself for the meeting. The young engineer, not yet 35 years old, had extensive professional experience and was a veteran from the trenches of World War I, yet he was completely awestruck by the figure of the Senatore, who – at less than 60 years of age – already had an aura of fame and detachment that set him apart from other members of the business world.

For Bonadé Bottino, Agnelli’s “stern face and scrutinizing gaze” will remain forever etched in his memory: it was the outward sign of an “indomitable will, forged by many years of far-reaching concrete achievements,” of a temperament that “had covered his relatively benevolent natural facial expression with the harsh mask he showed when addressing the employees.

” This is one of many portraits that are repeated with subtle variations, converging and blending into a profile of the great entrepreneur. The Senatore – as everyone referred to him – embodied an entrepreneurial ideal in the Italy of the 1920s, distilling in his own identity the traits associated with industrial leadership. Among the economic elite of Turin and Italy his position was special: no one doubted its significance. The Senatore was unique, like his creation, Fiat, a company that stands out from the crowd. He might have been isolated, too, in the context of Italy, a country still far from being an industrial power, but he wasn’t: because he also had the character and charisma of a leader.

When the Senatore had won public acclaim in his field, did his lifestyle keep him out of touch with others? When did the businessman Giovanni Agnelli, the brilliant former cavalry officer who would meet with friends interested in the new world of the automobile in the rooms of Caffè Burello, become “the Senatore,” the personality that inspired reverential respect?

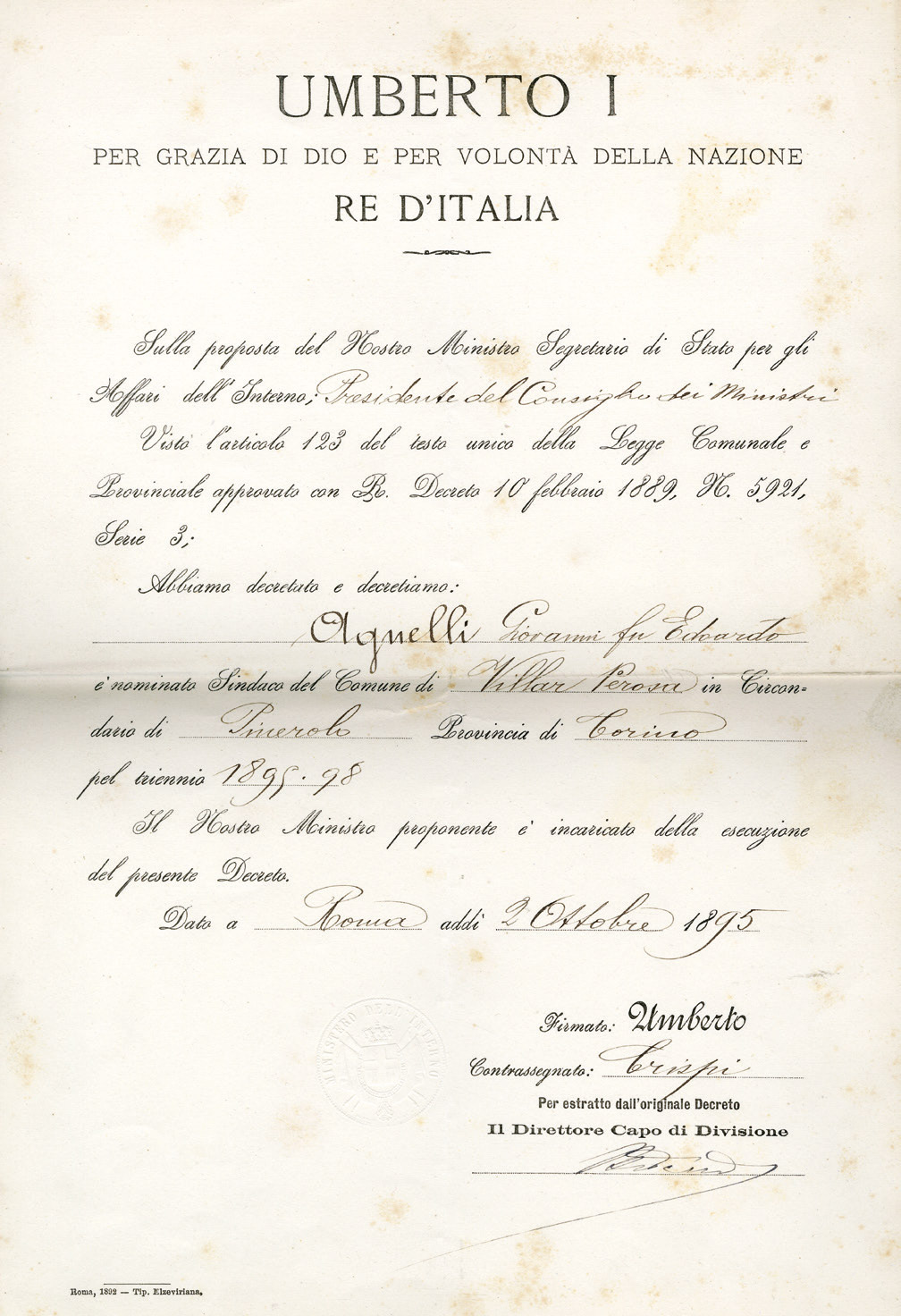

In fact, it happened very early, well before he donned the senatorial sash in 1923. What caused the leap forward was his innovative vision, which had already been clearly evident even before the Great War, in the 1910s.

The sharpest of the entrepreneurial leaders of that time understood it right away – for instance, the founder and the first president of the Industrial League of Turin as well as president of the Italian Industry Confederation, the Frenchman Louis Bonnefon-Craponne. He met Agnelli in the Fiat factory on Corso Dante after returning from a trip to the United States shortly before the war. Bonnefon-Craponne would refer to that meeting only later, in his book L’Italie au travail (1916), a sort of industrial report on Italy, which was gaining substance and importance.

According to the story, the visit to Fiat was an opportunity to see the industry’s future. In an environment that already seemed to have been conquered by the values of “modernity and scientific organization,” where the three elements of order, space and light reigned supreme, he interviewed Agnelli. In doing so, he kept one eye on “the opposite side of the street,” in which “an immense construction built of reinforced concrete lifts its three floors up to the blue sky”: it was the “colossal new ward of the large factory, which seeks to fight both the crisis and the competition with the perfection of its cars.”

“I have just come back from America,” said the founder of Fiat, “where I wanted to understand personally the danger that threatens not only the Italian industry, but also the French and German ones, too.” The problem was the increasingly fierce US competition, which would intensify the productivity gap between the two sides of the Atlantic.

“At Fiat,” explained Agnelli to his interlocutor, “we produce 3,000-4,000 cars a year, while Studebaker or Ford produce between 150,000 and 200,000!” Cars that were “less well-made, with less attention to detail,” and that surely couldn’t compare with those made at Fiat, objects his interlocutor. Agnelli’s reply was ready: “Of course, their cars are made on the assembly line. Our customers are not yet accustomed to settling for vehicles that can’t withstand prolonged use. Moreover, even the smallest pieces have to be polished and nickel-plated. When it comes to our cars, even the smallest details must be perfect – not only on the body but also in the engine and accessories.” But would this extreme attention to quality be enough to enable the European industry to meet the challenge of the American one? Agnelli doubts it: “Maybe,” he says, “it will soon be necessary to limit our customers to people who want to flaunt the luxury they can afford,” but “it is a small market, which would not be enough to support a production like ours”

At this point Bonnefon-Craponne raises the crucial question: “Couldn’t you introduce American manufacturing systems to Europe?” In other words, is the alternative the adoption of mass production, embracing the organizational principles of Taylor and Ford? But “Agnelli avoids answering. His eyes flash, then immediately darken, and his face […] remains impassive.”

Agnelli’s answer lies not in his public statements, but in an important business document like the minutes of a Fiat Board of Directors meeting. There one reads on 2nd June 1915, just over a week after Italy entered the war: “A magnificent new factory is the only way to deal with the domestic and foreign competition, allowing a reduction of prices, something which is only possible with increased production and a model factory.”

This was the announcement of the production plan that would culminate, in the early 1920s, with the construction of the Lingotto factory, at the time the largest car plant in Europe.

What distinguished the Senatore from other Italian entrepreneurs of his time and earned him a special aura of respect and prestige was his industrial vision, along with the determination to pursue objectives he considered indispensable: first of all, transplanting the mass production model to his factories, a goal towards which he would gradually direct all of Fiat’s energies. For him, the automobile industry really was “the industry of industries,” according to the famous definition that Peter Drucker coined in the 1940s, the sector on which the economic growth of the nation depended.

Agnelli wanted to rip the automobile system from the vicious circle of which it was still the victim in the period between the two world wars. If the number of consumers remained low and the market remained restricted, the price of a car would inevitably remain high: too high for the number of consumers to increase. For Agnelli “the problem of standardization is inherent in the development of the automobile,” as also stated in a study on the prospects of the automobile market in 1930. That’s why both the approach of manufacturers and the mindset of consumers needed to change: the car no longer being viewed as a luxury item, but as a means of transportation for “daily business.”

One can not understand the history of Fiat in the decades when the Senatore was at the helm, without bearing in mind this objective which was his north star: the search for technological, organizational and market conditions that would lead to the creation of the Italian version of the American model of mass production. Dante Giacosa, the designer of popular small cars (the Topolino, the 600, the 500), clearly demonstrated this with his long professional career.

Everything started that morning in late winter of 1933 when the engineer Antonio Fessia called Giacosa into his office on the top floor of the Lingotto building, and told him that the Senatore wanted him to design “a small, cheap car” to sell at the most affordable price possible. Did he feel up to the task of designing the chassis and the engine?

Giacosa just turned twenty-eight, responded enthusiastically to the challenge. Fessia, his boss, who was not much older than he was, evidently felt the weighty responsibility of what Agnelli had asked him to do, but his warning was met with great coldness by Giacosa, not least because he knew he was risking his whole future on this and he had a significant position to defend. Giacosa realized that this was his big chance, although he later confessed in his memoirs that he never really knew “why Senatore Agnelli had decided to entrust” to his office such a delicate project, which carried “the responsibility of directing the design of the compact economy car with which he intended to have Fiat make a decisive new leap towards mass production.” That was the real goal towards which Agnelli directed the best energies of the company, even in the most difficult periods of the Great Depression of the 1930s.

An honorary degree in Engineering from the Politecnico di Torino, in February 1937 (a little more than six months after the launch of the Topolino), was conferred on the Senatore in recognition of his work to develop an affordable car. The following June, to celebrate the event, the engineers of “the whole Fiat Group,” of riv of Villar Perosa, and those “scattered near and far in every part of the world” gave him an album of drawings by fourteen of the most significant artists of the time, such as Felice Casorati, Carlo Carrà and Francesco Menzio. The honor of presenting the album to the Senatore was given to the designer with the most seniority at Fiat, Celestino Rosatelli, the creator of many of the br and cr series aircraft, at Fiat since 1918. Rosatelli spoke on behalf of the company’s 300 engineers (out of a total of over 50,000 employees, of which 6,600 were office workers and managers).

Agnelli thanked Rosatelli for his kind words; Rosatelli was a man – he emphasized – “to whom Fiat [owed] all of its most important achievements in aviation,” which made him, “with his genius, exceeded only by his personal modesty, a worthy representative of the value of all our engineers, all of our technicians, with or without a degree.”

This expression – “with or without a degree” – is no accident, because the Senatore wanted to emphasize that the recognition of the Politecnico was well deserved by Fiat, as a “builder of technical values,” “nursery of constructive energies,” and “school of experience, from which many gifted and willing young men [had been] launched and launch[ed] themselves in order to increase, often with outstanding results, the wealth of inventions and applications of Italian engineering.” Agnelli, who’d “graduated four months earlier, despite having been at Fiat since 1899…” took care to point out that “a degree, the noble qualification of studies completed, of science learned in schools” was only “a starting point.” After that, “especially in the technical field,” it was a question of “graduating from the school of experience: working in the lab and the workshop.”

In this way, the Senatore wanted to show the primacy of production culture. It was forged in the factory day after day, by bringing together the knowledge of technologists with the practical, daily experimentation performed by countless company workers, with whom the designers were bound to cooperate. So yes, Agnelli praised the accomplishments of his designers, highlighting the work of an architect of Italian aviation like Rosatelli, but at the same time he took care to point out that mass production was the result of not only the drawing table, but also of factory experience. These together made it possible to introduce continuous improvements in production processes and products.

The Senatore was also careful to maintain a special relationship with the designers, whose prototypes of cars and aircraft were personally evaluated by him. This explains the special bond that united them, although it never resulted in a predominance of the design team within the company system. The technical universe was essential as were the design groups: but good business and strategic decision making required all these inputs to come together. For this reason the Senatore was always careful to spend his time with many groups across Fiat.

Sometimes he gave them attention so focussed that it astonished those involved. For example, Giuseppe Gabrielli – the most famous and respected name in Fiat aviation, the key figure in its history – recalls in his memoirs the many informal meetings with the Senatore, during the 1930s: “He often invited Rosatelli and me to his house for dinner and, after his wife, Donna Clara, had retired, we stayed up for hours talking about airplanes, wings, and structures. Sometimes he had us take him to a cabaret, where we finished the evening merrily.”

Neverthless, from its earliest years, the history of Fiat is studded with conflicts between Agnelli and the designers, such as the one that led to the break with Aristide Faccioli, the first technical director, who left in 1901. But even with his successor, the engineer Giovanni Enrico, the relationship was not easy. Agnelli never relinquished control of technical decisions; he was convinced that this was the essential prerogative of the entrepreneur.

The professional life of a Fiat engineer must not have been easy if we believe the stories contained in the autobiography of the other excellent designer, Giacosa. These describe a corporate technical world laced with personal and group rivalries and conflicts among the engineers: clashes between personalities, approaches and ideas from which flowed the technological evolution of Fiat, a reality marked by competition between individuals and between roles, over which reigned with absolute authority and unassailable calm, the final decision maker: the Senatore – who, as it turns out, was willing to devote a great deal of time to his technicians.

The Senatore received visitors in his office – recalls Giacosa – from behind his desk; it was “perfectly empty: not a sheet; not a letter; there was only one indelible pencil with which he signed the few letters that his secretary, Dr. Canova, brought him very discreetly.” Gabrielli often attended this “ceremony,” as he called it, when in the late afternoon Senatore would summon him “to talk about aviation.” Gabrielli continues: “I was worried about wasting his valuable time and one day I asked him: ‘Senatore, with all the work you have to do, how do you find time for these conversations?’ He replied: ‘Work? I don’t work, I only concern myself with what the others have to do.’”

To the designers, the head of the company seemed like a demiurge, who appeared to supervise the tasks of the technical staff with a dedication as constant as it was unflappable. He showed that he understood the problems they spoke to him about, but with a different understanding of things: his way of looking at things remained separate from theirs, because he saw their projects from a completely different perspective.

He could listen to the engineers talk for hours and hear them confront each other without letting it influence his final judgment, based on elements of assessment and vision controlled by him alone. And yet he did not fail to show, given the right opportunities, a sense of gratitude for the technical expertise on which the company depended. Eight years after the conferral of the honorary degree, Agnelli was able to reciprocate Rosatelli’s tribute. Rosatelli died aged 60 in September 1945. The Senator was also then near the end of his life – he would pass away in Turin on 16 December – but he had Gabrielli accompany him across Turin, still a little eerie immediately after the war, to the house of the deceased in a building where the elevator was not working. Supported by Gabrielli, he slowly climbed three flights of stairs. He then, “kissed the corpse, said a few words of comfort to the family and then left…” This was the ultimate proof of a collaborative bond that had developed over decades at Fiat.

In the period between the wars, Fiat operated with a reduced team of directors, centered around the figure of the Senatore, increasingly supported by Vittorio Valletta. Agnelli, interested in every detail, was the critical interlocutor of the designers: he pressed them – but at the same time supported them – in their work, putting them constantly to the test by attending the presentation of their prototypes, of which he was the ultimate judge.

Gabrielli has vividly described the atmosphere of looming trepidation each time the Senatore boarded a plane for a test flight. In the aeronautical field, as in the automotive field, those outings focused on another protagonist: in addition to the leader of Fiat and the designers: the test pilot, who played a crucial role in revealing the strenghts and weaknesses of a new product, and highlighting the corrections required. It was then up to the designers to interpret those remarks so that they met the technical parameters.

It was really a ritual, central to the symbolism of company life, because of its character: not only was it an essential moment of verification, it was also central to the relationship of the designers with the Senatore. Indeed this relationship freed them from their hierarchical subordination to production managers – to the point that the young Giacosa learned to evaluate the career and the professional fortunes of his bosses, beginning with engineer Fessia, based on the regularity with which they, at about five o’clock in the afternoon, went into the Senatore’s office.

The competitive atmosphere in which the technical departments of the Fiat operated, regulated by Agnelli’s authority, was not written in the dna of the company. It was rather, at least in part, the result of a strategic plan, dictated by specific market conditions and geared to creating competition between operational functions in order to bring out the best in them.

This tension was also related to the objective that Agnelli had had in mind since his travels to America at the beginning of the century: Fiat and European industry had to assimilate the American lesson and take on the goal of mass production. It was to this end that the Senatore, through a chain of incremental innovations, meant to lead his enterprise. Achieving this meant pushing the whole of Fiat: pulling it out of the rigidity of the past. The entire company would then benefit from this shared vision, able to put together the work of the various organizational functions, mobilizing and promoting all their energies as one.

For thirty years, Giovanni Agnelli measured his leadership against this strategy, achieving in June 1936 (“a memorable date for Fiat,” according to Giacosa) the launch of the “mass production for which the Lingotto factory had ultimately been built.” Then “the production rate rapidly reached 100 cars a day” noted Giacosa, justifiably proud of the success of his Topolino. Certainly, a substantial productivity gap with the US industry remained, but the technicians of Fiat were convinced they were on the right path to create a successful mix of products and technologies for the mass market.

The World War II and its consequences brought plans for expansion to a prolonged halt. Nevertheless, the work led by the Senatore – that feverish season of preparation – built the platform from which in the 1950s and 1960s Fiat could fully deploy its technological, industrial and management skills.

Giuseppe Berta